Jacob Springer — Jan 17, 2022

A recently published paper by Carter et al., 2021 suggests that neural network image classifiers overinterpret images, meaning that the classifier finds evidence for the correct class label based on non-human-interpretable patterns that are present in small subsets of pixels from the unmodified images. Carter et al. argue this idea by finding so-called Sufficient Input Subsets (SIS) and demonstrating that images that contain only these subsets are confidently and correctly labeled by the classifier. Since standard neural network image classifiers can only take as input an entire image, an image containing only a subset of pixels must replace the “removed” pixels with a color that is expected to have no effect on the output. The authors choose gray. The authors claim that the high confidence of image classifiers on SIS images arises from the non-human-interpretable but predictive content of the retained pixels in each SIS image. In this article, I will argue that this is not the case. Instead, I will argue that the “removed” (i.e., gray) pixels introduce adversarial-example-like patterns that cause the classifier to confidently classify the input. In fact, I will argue that classifiers do not find class evidence in the retained pixel subsets alone. Additionally, I will show that the algorithm proposed by the author can be used to construct adversarial SIS images that are confidently but incorrectly classified. This article highlights an example of the difficulty of interpreting neural network classifiers.

A recently published paper titled Overinterpretation reveals image classification model pathologies (Carter et al., 2021) argues that neural network image classifiers can often classify images correctly with only a tiny non-human-interpretable subset of the pixels of the original image. The authors argue that this result supports the idea that neural network classifiers overinterpret the input images—that is, the classifier finds sufficient evidence for the class label in restricted areas of the image that lack human-interpretable patterns.

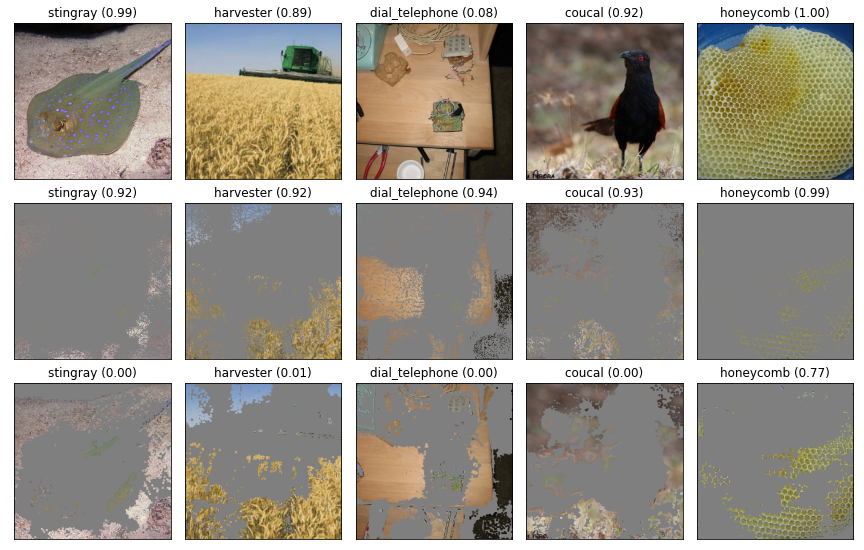

Figure 1. Carter et al.'s evidence for neural network overinterpretation. This figure is a reproduction of Figure 4 from Carter et al. (2021). This figure shows the original images (top, from the [ImageNet](https://image-net.org) dataset) and the Sufficient Input Subset computed by the BGSIS method (bottom). Each Sufficient Input Subset image consists of a sparse set of unmodified pixels from the original image, where the remaining pixels are set to gray. Each Sufficient Input Subset image is confidently classified as the true label (shown above original images).

The authors present an algorithm called Batched Gradient SIS (BGSIS) to find an image containing only a sparse set of unmodified pixels from an original image such that the classifier confidently classifies the new image correctly. The resulting image is called a Sufficient Input Subset (SIS) image. Importantly, neural network image classifiers can only take as input an entire image. Thus, a pixel can be “removed” from the image by setting it to a color which is expected to have no effect on the classifier. A seemingly reasonable choice for such a color is the average color across every pixel in the dataset—gray. Thus, each image found by the algorithm consists of a sparse set of unmodified pixels and the remaining pixels which have been set to gray. Examples of SIS images are presented in Figure 1 in the bottom row. BGSIS iteratively removes pixels (by setting pixels to gray) that least decrease the confidence.

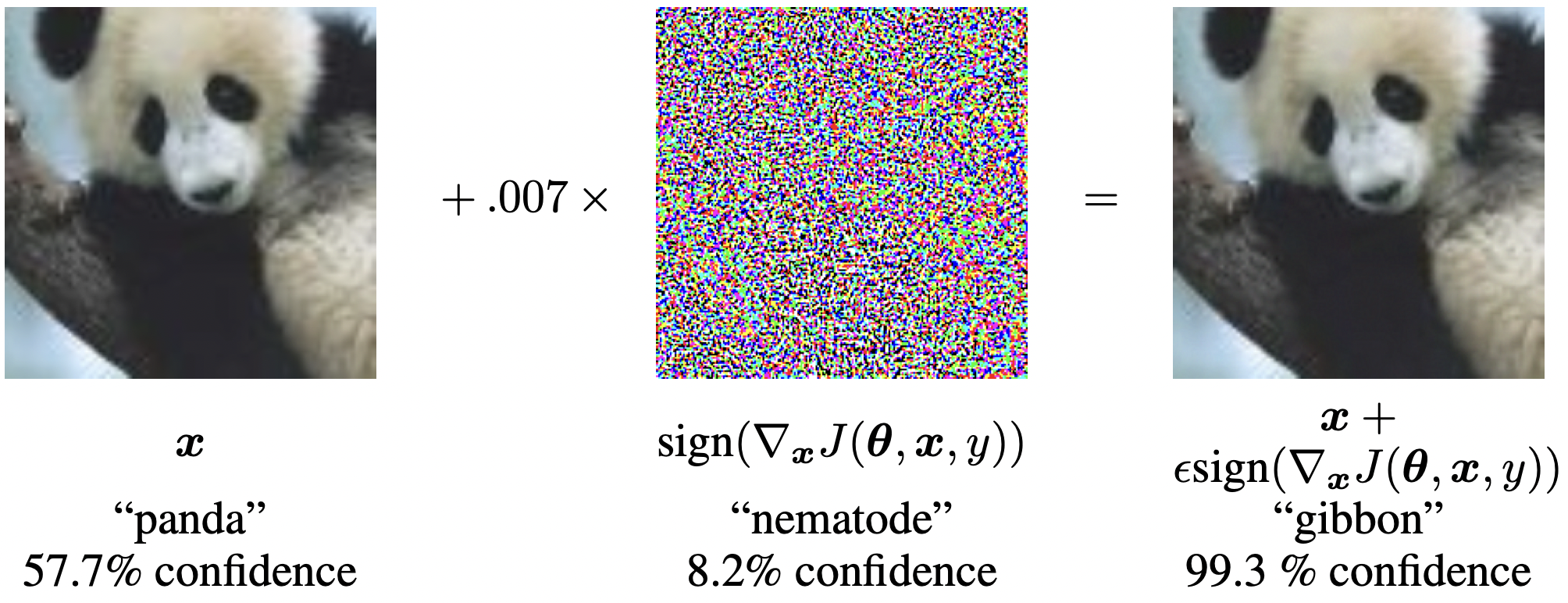

Figure 2. The iconic figure from Goodfellow et al. (2015) conceptually illustrating an adversarial example. The original image of a panda (left) is correctly classified by the neural network. However, it can be perturbed by a non-human-interpretable pattern (center), to form an adversarial example (right), which is semantically indistinguishable from the original image, but is confidently misclassified by the neural network as a gibbon.

The idea that neural networks can find class evidence from non-interpretable patterns is not new. Neural networks are well-known to be susceptible to adversarial examples (see Szegedy et al. (2014), Goodfellow et al. (2015), and Figure 2), in which small non-interpretable perturbations to an image cause the classifier to confidently but incorrectly label the image. Carter et al. argue that, unlike adversarial examples, the existence of confidently-classified SIS images suggest that classifiers find strong class-evidence in the non-interpretable but predictive areas of the original image, rather than added components.

In this article, I will argue that this is not the case. I will show that the set of pixels that BGSIS discovers as “sufficient” are often not sufficient, and rather it is the patterns introduced by the “removed” (i.e. gray) pixels that add information to the image to maintain or increase the confidence of a particular class. I will conclude by arguing that the patterns introduced by these removed pixels act like adversarial examples.

Carter et al. argue that the image classifier finds evidence for its classification in the pixels that are identified by BGSIS as a Sufficient Input Subset. Here, I propose a modified experiment to control for the possibility that the “removed” (gray) pixels introduce patterns that might affect the classification score. I will retain every pixel that is identified by BGSIS as part of the SIS, and thus we should expect that if the SIS is sufficient for classification, then the classifier should continue to classify the image correctly with high confidence.

The experiment is as follows: first, I will run BGSIS to find an SIS, and then, I will “smooth” this subset by reintroducing pixels that are adjacent to pixels in the original SIS, i.e., I will uncover the gray pixels that are at the border between the gray and non-gray regions. I call the resulting image a Smoothed Sufficient Input Subset (SSIS). If the classifier finds evidence in the gray pixels adjacent to non-gray pixels in the SIS image, then smoothing the SIS image will remove this evidence. Carter et al.’s interpretation suggests that removing this evidence will not affect the classifier confidence but I will show that nearly all class evidence lies in these gray pixels.

Figure 3. Examples of the original images (top), the SIS images (center), and the SSIS images (bottom). Above each image is the true label and the classifier's confidence of this label when evaluated on the image. The smoothing process re-introduces pixels that are on the border between gray regions and non-gray regions, thus reducing the high frequency patterns created by the gray pixels in SIS images. Every non-gray (i.e., retained) pixel in a SIS image is also kept non-gray in the corresponding SSIS image. This means that the smoothing process to transform SIS images into SSIS images should not remove any class-evidence from the subset of pixels that are retained by the SIS. The key takeaway from this figure is that both the original images and the corresponding SIS images are (almost always) confidently classified as the true label, however, the classifier confidence of the true label on the SSIS images is near zero, suggesting that the evidence for the true label is not contained in the retained pixels, but rather the patterns introduced by the gray pixels on the border between gray regions and non-gray regions.

The results of this experiment, shown in Figure 3, demonstrate that while the true-label confidence of the classifier is high for the original and SIS images, the confidence for the SSIS images is near-zero. The primary difference between the SIS images and the SSIS images is that, for the SSIS images, we remove the high-frequency patterns introduced by gray pixels adjacent to SIS pixels. Thus, the near-zero classifier confidence of true labels for the SSIS images suggests that the confidence of the classifier on the SIS can be, in large part, attributed to the high-frequency patterns introduced by the gray pixels themselves. Furthermore, each SSIS image contains every pixel that is included in the corresponding SIS but these images are nonetheless misclassified, which implies that each SIS is not sufficient for classification.

The following experiments demonstrate that SIS images generated with the BGSIS algorithm can be thought of as adversarial examples: the BGSIS algorithm introduces patterns into the image by “removing” (coloring gray) pixels in a way that increases the confidence of the true label by way of gradient ascent. Thus, the classifier confidence in the true label on SIS images is often substantially higher than the corresponding classifier confidence on the original image. Furthermore, BGSIS can be modified to increase the classifier confidence of an arbitrary class label, thus creating adversarial SIS images.

First, I present a visualization of the BGSIS algorithm, reimplemented by me, and the classifier confidence associated with the image at each step. In addition, I present the classifier confidence for each iteration of the algorithm. BGSIS runs by iterative choosing the best pixels to remove (color gray) in batches until every pixel is removed. The algorithm outputs the image with as many removed (gray) pixels as possible so that the confidence remains above a preset threshold.

Figure 4. Animated visualization of the BGSIS algorithm and corresponding classification confidence over each iteration in the algorithm for ten different initial images. The first image in each set is the original image, the second image has pixels removed corresponding to the pixels that would be removed at the current iteration, and the graph to the right is the classifier confidence of the true label (above the graph). The key takeaway from this figure is that, for each image, the classifier confidence of the true label increases to near 100% as the algorithm progresses.

There are two key takeaways from Figure 4:

These results suggest that the BGSIS method is essentially a search for an adversarial set of gray pixels in an image. The algorithm operates by computing the gradient of the confidence with respect to the image, and then removes (colors gray) pixels to minimally decrease (which, in this case, is the same as to maximally increase) the confidence. Broadly, this is the same structure as a gradient-based search for an adversarial example. Thus, it is no surprise that this algorithm will act similarly to any adversarial example search algorithm.

The authors include a similar figure to my Figure 4 in the appendix of their paper (Figure S15 from their paper). Their figure illustrates the classifier confidence for each iteration of the algorithm, and includes substantially more data than our Figure 5. Similarly to my Figure 4, they find that the classifier confidence on the true label of each image almost always increases quickly to nearly 100%.

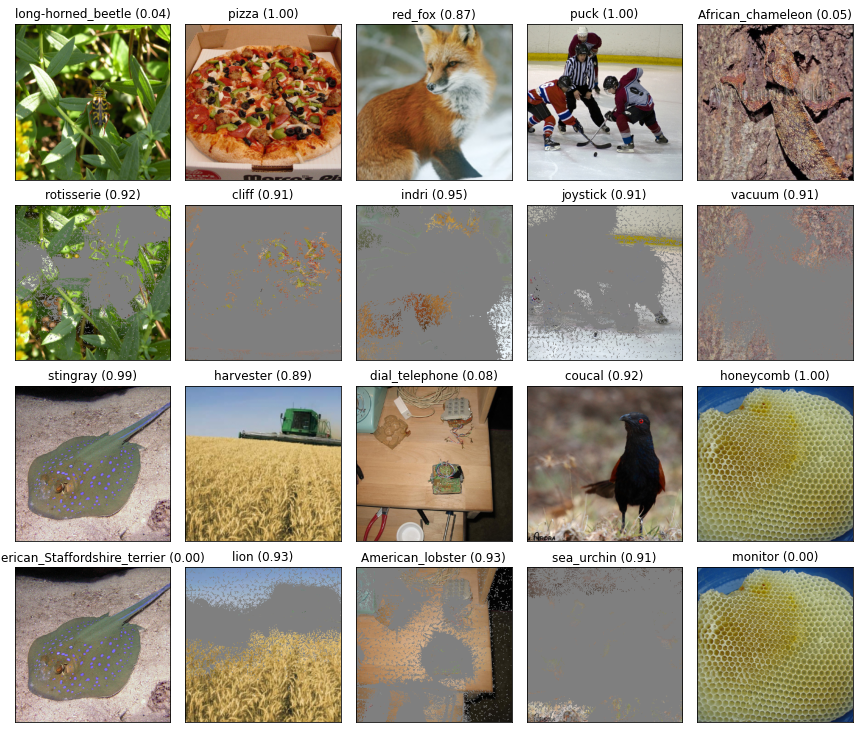

To explore the idea that this method can be used to construct adversarial SIS images in more depth, I construct explicitly-adversarial SIS images using the BGSIS algorithm with the goal to cause the classifier to identify a particular (adversarial) target label with a confidence above 90%. That is, instead of removing pixels to increase the confidence of the true label of the image, I remove (color gray) pixels to increase the confidence of the adversarial target label.

Figure 5. Class-targeted adversarial SIS images generated using BGSIS. In each pair of rows, I render the original image and the confidence on the true label (top) and the adversarial image and the confidence on the adversarial target label (bottom).

These adversarial SIS images—shown in Figure 5—have similar properties to the original SIS images from Figure 1: for many of the examples, the confidence of the classifier is above 90%, and most of the image has been removed (set to gray). Consistent with our previous experiments, the existence of adversarial SIS images suggests that the removed (gray) pixels themselves carry information pertinent to classification.

To illustrate this idea visually, I present (admittedly, somewhat cherry picked) SIS images generated using adversarially-trained classifiers which are known to have more-human-aligned gradients (Engstrom et al., 2019).

Figure 6. Original images (top) and SIS images generated using BGSIS on an adversarially-trained ResNet50 (bottom).

The removed pixels form interesting patterns that appear semantic when the classifier is robust (Figure 6). The semantic nature of the removed pixels are not (always) an artifact of outlining a semantic feature present in the original image, and instead, can create semantic looking patterns that are not present in the original image. For example, the image of the ears of corn are masked to appear as ears of corn that do not align with the original ears of corn. Similarly, the image of the baseball is masked to include the appearance of a larger baseball than appears in the original image. The image of the panda is masked to include the appearence of either whiskers or possibly long thin bamboo-type leaves. While this experiment is less rigorous, it demonstrates visually how removed pixels can form patterns that are meaningful to the classifier.

Carter et al. find that they can train models on the 5% pixel-subset images that attain minimal accuracy loss compared to the original models and they conclude that the 5% pixel subset has real statistical patterns that correlate with the label well enough on which to base a prediction. I would suspect that a better experiment to determine if this is true would be to train on the SSIS images from above, although it is not an experiment that I will present here due to the computational cost of training a new model. As an alternative hypothesis to Carter et al., it is possible that, instead of the 5% remaining pixel subset, the patterns generated by the removed (gray) pixels are real statistical patterns that are useful for classification. The idea that you can train a classifier on adversarial examples and yield non-trivial generalization accuracy has been shown by Ilyas et al. (2019) in the paper Adversarial Examples Are Not Bugs, They Are Features. A result suggesting that training on the adversarial patterns introduced by the removed pixels of sufficient input subsets generated by BGSIS would be consistent with Ilyas et al.

Carter et al.’s paper raises a very important point: be cautious about attempts to interpret a deep learning model, as the results are often subject to the bias of the interpretation algorithm.

I don’t think that the results that the authors present are wrong or uninteresting—quite the contrary. It is striking that 95% or more of the pixels in an image can be replaced with gray and that a classifier will maintain confidence in its classification. However, unless there is a way to explicitly remove input from the model, the interaction between the removed input and the remaining input, such as the patterns made at the border of the removed grey pixels, will always have a possibility of affecting the behavior of a classifier.

Perhaps a better approach would be to define a sufficient input subset as a subset of pixels such that, if present, will always cause the classifier to confidently predict the label under any perturbation to the other pixels. I doubt this will be useful, first because I would speculate that such a set would be difficult to compute, and second because neural networks are so vulnerable to adversarial examples that such a set would likely consist of nearly every pixel in the original image, so as to not introduce many degrees of freedom that might allow a vulnerability to arise.

I would speculate that similar approaches to interpretability that aim to determine the contribution of individual pixels will be vulnerable to similar explanations in terms of adversarial examples.

The code to reproduce my experiments is available at my GitHub page.

The classifiers I used were downloaded from this repository from Microsoft. I used the standard ResNet50 (ɛ=0) and an adversarially-trained ResNet50 (ɛ=3).

All images you see in this article are from ImageNet.

Carter, B., Jain, S., Mueller, J., & Gifford, D. (2020). Overinterpretation reveals image classification model pathologies. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 34.

Szegedy, C., Zaremba, W., Sutskever, I., Bruna, J., Erhan, D., Goodfellow, I., & Fergus, R. (2014). Intriguing properties of neural networks. 2nd International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2014.

Goodfellow, I. J., Shlens, J., & Szegedy, C. (2015). Explaining and harnessing adversarial examples. 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2015.

Engstrom, L., Ilyas, A., Santurkar, S., Tsipras, D., Tran, B., & Madry, A. (2019). Adversarial robustness as a prior for learned representations. arXiv preprint arXiv:1906.00945.

Salman, H., Ilyas, A., Engstrom, L., Kapoor, A., & Madry, A. (2020). Do adversarially robust imagenet models transfer better?. arXiv preprint arXiv:2007.08489.

Ilyas, A., Santurkar, S., Tsipras, D., Engstrom, L., Tran, B., & Madry, A. (2019) Adversarial Examples Are Not Bugs, They Are Features, Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 32.